|

| Rose 'Wild Eve' © Debs Cook |

I have a very, very soft and fragrant spot for roses, their heady fragrance, vibrant colours and their silk or sometimes velvet like textures have captivated me since I was a young girl, but the roses have to be fragrant to for me or they are pointless, roses delight the senses with their aroma. In the garden I have many roses, less now than I used to have, and as the garden is being redesigned there is scope to add more, and you can bet that whichever ones I do plant will be fragrant.

The first documented medicinal use of the rose occurred in Theophrastus' ‘Historia Plantarum’ written around the 3rd century B.C. in which he described the properties of the ‘hundred-petalled rose’. By the 1st century A.D. Dioscorides included remedies in his ‘De Materia Medica’ for rose salves and preparations that could treat the eyes, ears, gums and even soothe the intestines, he also described the manufacture of ‘Rhodides’, which were small pomanders made from powdered rose petals, spikenard and myrrh which he said were ‘worn around women’s necks instead of necklaces’ and were primarily used to disguise the smell of body odour. Pliny the Elder also from the 1st century A.D. described 12 varieties of roses that grew in Greece, the most often quoted is his ‘Milesian Rose’ which by its description was most likely the rose we know today as Rosa gallica or the Damask Rose.

This article on the way herbalists and cooks have used the rose over the centuries was inspired by ‘Rose Recipes from Olden Times’ an old book written by Eleanour Sinclair-Rohde in 1939, Rohde is one of the female 20th century herbal authors that I have been researching this past few weeks for an article I will be uploading soon. As I re-read the opening to the book it struck me that a lot of what she said back in 1939 still rang true today. ‘In the days when Roses were valued more for their fragrance, sweet flavour, and medicinal virtues than for their beauty, the petals were used in countless ways. Most folk associate flower recipes with old vellum-bound volumes and regard the recipes therein contained as being of little more than antiquarian interest. Indeed the phrase "Rose recipes" conjures up visions of sixteenth and seventeenth century still rooms, busy housewives and attendant maids in picturesque costumes bringing in great baskets of freshly gathered Roses. It is true that many of the old recipes or "receipts" as the word was more commonly spelt are too complicated for these hurried times but many are simple and practical.’

When you think of the ways our ancestors used the rose to scent their homes in times gone by it makes you hanker for those fragrant days, well at least in part! Dried rose petals were laid among clothes and linens, the powdered petals were added to home made candles, they made rose pot-pourri and sweet bags, Ms Rohde informs us of that fact adding that ‘rose petals figured largely in the old sweet bags used not merely for scenting linen but to hang on wing arm-chairs. ‘The mixture of dried Rose petals, mint leaves and powdered cloves recommended in ‘Rams Little Dodeon’, 1606 has a most pleasing fragrance.’

Cosmetically they used roses to make soaps, face powders, perfumes, ointments, creams, vinegars, lotions and scented waters. They cooked with them, using them to make conserves, jellies, cakes, puddings, sauces to accompany both sweet and savoury dishes, made wine with them and sweets treats such as Turkish delight. So many of those uses have disappeared in households across the UK today, as people favour buying mass produced food, cosmetics and cleaning products, but it’s simple to make your own, just look to the past and adapt those recipes for the future.

In part one I'll begin by looking at 16th, 17th and 18th century rose uses and continue with the 19th to 21st centuries in part two. The English poet and writer Gervase Markham, born in Cotham ca 1568, Nottinghamshire wrote ‘Countrey Contentments or The English Huswife’ published in 1623 in which he recommended a rose based remedy to cure the ‘frenzy’ which he described as arising from a ‘hot cause’. When this occurred Markham instructed the reader to ‘rub the browes and all his head over with oyle of Roses, Vinegar, and Populeon [an ointment made from the buds of the Black Poplar tree (Populus nigra)].

16th Century Recipes

Rose Water - Anthony Ascham a 16th curate, astrologer and botanical writer from Yorkshire, published a herbal in 1550 ‘A Lyttel Herbal of the Properties of Herbs, &c. made and gathered in the year 1550’, which included his recipe for making Rose Water.

‘Some do put rose water in a glass and they put roses with their dew thereto and they make it to boile in water, then they set it in the sune tyll it be readde and this water is beste.’ Ascham also added his observation that ‘drye roses put to the nose to smell do comforte the braine and the harte and quencheth sprites.’ - Anthony Ascham's, 1550.

|

| Sweet Briar Rose (Rosa rubiginosa) © Debs Cook |

A few years after Ascham’s book was published, Sir Hugh Platt was born, Hugh grew to be a well-respected author and inventor in 16th century London, he was one of Elizabeth I courtiers an accomplished gardener who wrote about agriculture. He was also a collector of receipts for preserving fruits, distilling, cooking, housewifery, cosmetics, and the dyeing of hair. The word receipt is an old word for recipe and was often used to differentiate between a culinary and medicinal recipe.

One of Platt’s recipe books ‘Delightes for Ladies: to adorn their persons, tables, closets, and distillatories with beauties, banquets, perfumes and waters’ included several delightful recipes using both fresh and dried roses. The recipe below is Platt’s version of a scented sachets which during the Middle-Ages were referred to as a ‘plague-bag’, then they were used to keep parasites and disease at bay, by Platt’s time they were being used to fragrance linen and clothing, so became more floral and ‘sweet’ in fragrance.

‘Take of Red and Damask Rose-leaves of each two ounces, of the purest Orris one pound, of Cloves three drams, Coriander seed one dram, Cyprus and Calamus of each halfe an ounce, Benzoin and the Storax of each three drams; beat them all save the Benzoin and the Storax and powder them by themselves, then take of Muske and Civet, of each twentie graines, mix these with a little of the foresaid powder with a warm Pestle, and so little by little you may mix it with all the rest, and so with Rose leaves dried you may put it up into your sweet Bags and so keepe them seven yeares.’ - Sir Hugh Platt, 1594.

N.B. Platt refers to rose leaves in this recipe, the recipe was in actual fact calling for rose petals. Often in old books and manuscripts up until the early 18th century, rose petals are referred to as leaves, this was due to the fact that the old roses popular in the receipts of the day were referred to as the ‘Cabbage Rose’ or ‘Cabbage Leaved Rose’. The exception to the rule is when recipes for making tea using wild roses were documented, those teas actually used the green leaves of the wild rose in their making.

By the late 16th century, John Gerard included descriptions for 6 varieties of roses, concluding that the Damask Rose was the best kind to use for scent, ‘meat and medicine’. Gerard like many before him believed that the distilled water of roses was good for the ‘strengthning of the heart, and refreshing of the spirits, and likewise for all things that require a gentle cooling’. He also described using the rose water to flavour junket, cakes and sauces and its use to soothe the eyes ‘It mitigateth the paine of the eies proceeding from a hot cause, bringeth sleep, which also the fresh roses themselves provoke through their sweet and pleasant smell.’

17th Century Recipes

|

| Damask Rose (Rosa × damascena) © Debs Cook |

Like Gerard before him, Culpeper believed the Damask Rose was the most aromatic rose, he described uses for a syrup made from the damask rose that was an excellent purgative that was good for ‘purging choler’, although I’m positive that the super charged version of his recipe with added fly agaric would not make it in to herbal remedy books of today.

King Edward VI's Perfume

17th century recipes for roses included many recipes for perfuming the home, one such recipe appeared in ‘The Queen's Closet Opened’ which was first published in 1655 and is credited on to a W.M. who was cook to Queen Henrietta Maria, wife of Charles I. The book was a phenomenal success allegedly containing the recipes that had been enjoyed by the royal family over the years and before the dawn of the 18th century it had been reprinted 10 times. Sweet waters such as the one in the recipe below were used to perfume the air and as washing waters for the hands.

‘Take twelve spoonfulls of right red rose water, the weight of six pence in fine powder of sugar, and boyl it on hot Embers and coals softly and the house will smell as though it were full of Roses, but you must burn the Sweet Cypress wood before to take away the gross ayre.’ - W. M., 1655.

|

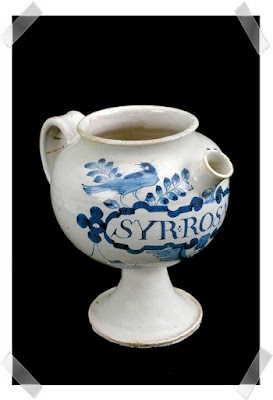

| Syrup jar used for Syrup of Roses, England, 1670-1740. Credit: Science Museum, London. |

Another popular work of the 17th century was ‘The Art of Distillation’ first published in 1651 and written by John French who described himself as a Dr. of Physick, the work was published in six volumes. In volume 2 a variety of waters both medicinal and cosmetic containing rose petals were described, these included ‘Bezeard Water’, ‘Dr. Stephen’s Water’, ‘Aqua Imperialis’ and ‘Dr Mathias Palsy Water’.

John French was a respected English physician who practised and studied during the time that alchemy was fast becoming the credible science of chemistry. He was well known for his extensive knowledge of chemistry and was respected by scientists of the time such as the chemist and physicist Robert Boyle.

‘Take of Damask, or Red Roses, being fresh, many as you please, infuse them in as much warm water as is sufficient for the space of twenty four houres; then strain, and press them, and repeat the infusion severall times with pressing, until the liquor become fully impregnated, which then must be distilled in an Alembick with a refrigerator, let the Spirit which swims on the Water be separated and the water kept for a new infusion. This kind of Spirit may be made by bruising the Roses with Salt, or laying a laye of Roses, and another of Salt, and so keeping them half a year or more, which then must be distilled in as much common water or Rose water as is sufficient.’ John French, 1651.

18th Century Recipes

Sir John Hill wrote of four types of roses the Wild or Dog Rose then known as ‘Rosa sylvestris’ now known as ‘Rosa canina’ a tea of the buds he described as being ‘an excellent medicine for overflowings of the menses’. Of the Damask Rose (Rosa damascena) he recommended that the flowers were turned into syrup which he credited with being ‘an excellent purge for children’ adding that there was ‘not a better medicine for grown people, who are subject to be costive [constipated]’. Of the White Rose (Rosa alba) he credited it with the same properties as the wild rose being an excellent treatment for heavy menstruation, adding that the white rose was also good against ‘the bleeding of the piles’. The same properties were ascribed to the Red Rose (Rosa rubra), a tincture made from this type of rose Hill believed strengthened the stomach and ‘prevents vomitings, and is a powerful as well as a pleasant remedy against all fluxes [dysentery].’

To Make Rose Drops

Eliza Smith was the author of a classic 18th century book known as ‘The Compleat Housewife, or Accomplish'd Gentlewoman's Companion’ which was similar in content to Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management published in the 19th century. Smith’s book, first published in 1727 contained culinary recipes, instructions for home decorating, tips on dealing with household problems like removing mildew, and it also included receipts for home remedies for treating a variety of ailments common at the time, such as smallpox.

Eliza was a housekeeper to some of the most fashionable and well to do families of the early 18th century, she died around 1732 but her book was reprinted 18 times after her death, and was one of the most popular domestic books of the 18th century, and is reputed to be the first English cookery book to be published in America in 1742.

‘The roses and sugar must be beat separately into a very fine powder, and both sifted; to a pound of sugar an ounce of red roses, they must be mixed together, and then wet with as much juice of Lemon as will make it into a stiff paste; set it on a slow fire in a silver porringer, and stir it well; and when it is scalding hot quite through take it off and drop in small portions on a paper; set them near the fire, the next day they will come off’. - Eliza Smith, 1727.

Method of Scenting Snuff

|

| Five young women taking snuff. Stipple print circa 1825. Credit: Wellcome Collection. |

It wasn't just men that partook in a sniff of snuff, many women indulged in the practice as you can see from the stipple print here. Later in 1761 Sir John Hill concluded nasal cancer could develop if people used snuff; he reported five cases of 'polyps, a swelling in the nostril adherent with the symptoms of open cancer'

In 1772 an English translation of ‘Le Toilette de Flore’ written by Pierre-Joseph Buchoz, a French physician, lawyer and naturalist appeared in London, containing remedies and skin preparations for most ailments that the lady of the day would have relied on to keep her family well appeared under the title of ‘The Toilet of Flora’. Amongst the recipes were ones scented with roses which including floral snuff recipes.

‘The flowers that most readily communicate their flavour to Snuff are Orange Flowers, Musk Roses, Jasmine, and Tuberoses. You must procure a box lined with dry white paper; in this strow your Snuff on the bottom about the thickness of an inch, over which place a thin layer of Flowers, then another layer of Snuff, and continue to lay your Flowers and Snuff alternately in this manner, until the box is full. After they have lain together four and twenty hours, sift your Snuff through a sieve to separate it from the Flowers, which are to be thrown away, and fresh ones applied in their room in the former method. Continue to do this till the Snuff is sufficiently scented; then put it into a canister, which keep close stopped.’- Pierre-Joseph Buchoz, 1771.

The recipes above represented a tiny fraction of the ones that are contained in old medical texts and reciept books, I may revisit the rose recipes from the 16th to 18th centuries in the future, part 2 of this article will follow soon and will look at 19th and 20th century rose recipes, and will conclude with a look at the modern way roses are used in the 21st century.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for you comment, I'll make it live as soon as I can and get back to you if required.